What is the New Normal for Mortgage Rates?

Since the 2008 financial crisis, global central banks have played a pivotal role in stabilizing financial markets through unconventional policies. Quantitative easing (QE)—where central banks purchase government and corporate bonds—became the favoured tool of the world's leading economies. By holding down interest rates and flattening yield curves, these central banks created an environment where borrowing became cheap and plentiful, particularly in housing markets.

But such largesse has had consequences. Inflation has reared its head, triggered by pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions and massive fiscal spending, forcing central banks to pivot towards quantitative tightening.

As they now reverse their once-dovish policies and interest rates rise, many are asking:

Will mortgage rates return to the ultra-low levels of the past,

or are we entering an era of permanently higher rates?

The future of monetary policy is deeply uncertain. While central banks aim to bring inflation back under control, they are also wary of causing recessions. In this delicate balancing act, where might rates land? And what does the next chapter hold for global finance, particularly for mortgage markets, where rates have already begun climbing?

The Return of Inflation

Between 2008 and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, advanced economies enjoyed a prolonged period of low inflation. Central banks, especially the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the Bank of Japan (BoJ), had kept interest rates at historically low levels to stimulate investment and consumer spending.

But COVID-19 changed the script. Governments unleashed unprecedented fiscal stimulus, and central banks doubled down on quantitative easing. Mortgage rates in Canada fell to 2% in 2020—a level almost unthinkable pre-pandemic.

In 2021, however, inflationary pressures began to mount. Supply chains, disrupted by the pandemic, struggled to keep up with surging demand. Energy prices spiked, exacerbated by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Central banks, who had maintained that inflation was "transitory," were forced to act when it became clear that price pressures were sticking around.

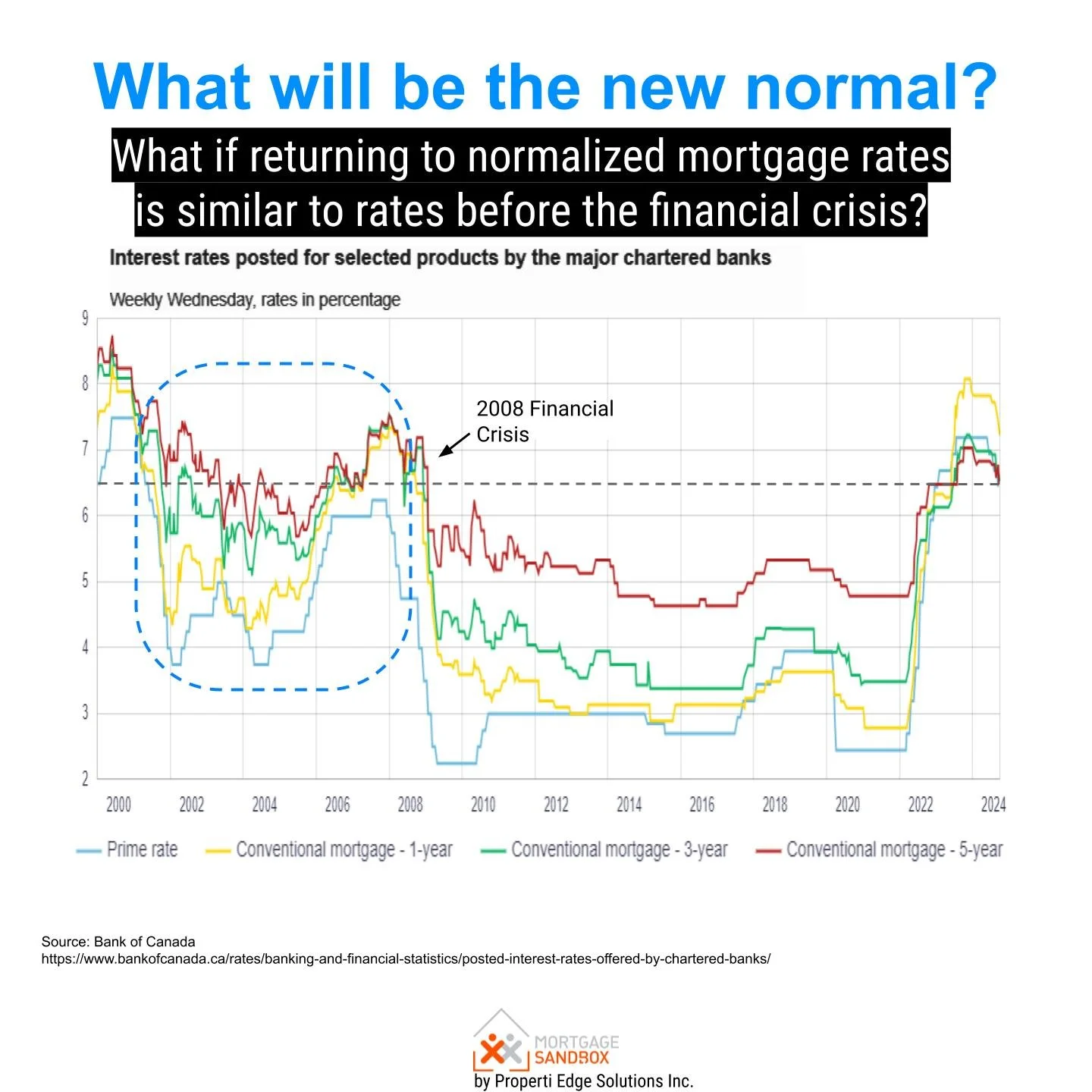

The Federal Reserve and the Bank of Canada led the charge with a series of aggressive rate hikes beginning in the Spring of 2022. By mid-2023, interest rates were the highest they had been in decades, marking a stark reversal from the ultra-low-rate world that had prevailed for years. Variable mortgage rates in Canada surged past 7%, a level not seen since before the financial crisis.

What Next for Mortgage Rates?

Predicting the future of mortgage rates depends heavily on the lessons the Bank of Canada takes away from the preceding 15 years of ultra-low rates. Broadly speaking there are two schools of thought.

Optimists: Back to Pre Pandemic Rates

The first, more optimistic view is that once inflation comes back under control, the Bank of Canada and other central banks will lower rates again, allowing mortgage rates to fall back to lower more affordable levels. Economists like Paul Krugman, who argue that the inflationary pressures of 2021 and 2022 were primarily the result of temporary supply-chain disruptions, support this view. Once these issues are resolved, inflation will fall, and central banks can ease up on their tightening.

Pessimists: Back to Pre Financial Crisis Rates

But others are less sanguine. Economists like Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan, authors of The Great Demographic Reversal, argue that inflationary pressures are here to stay. They point to structural changes in the global economy, such as aging populations, shrinking workforces, and the push towards deglobalization, as factors that will keep inflation elevated in the coming years. If they are correct, the Bank of Canada will be forced to maintain higher interest rates for longer, pushing mortgage rates up permanently.

On the Fence: Rates will end up somewhere in the middle

Between these two poles lies the more cautious middle ground, occupied by the likes of Olivier Blanchard and Larry Summers. They argue that while inflation will likely subside, the era of ultra-low rates is over. "We are unlikely to return to the post-financial crisis world of 0% interest rates and 2% mortgage rates," said Summers at the 2023 IMF meetings. Instead, they envision a "new normal" where rates settle at a higher level than before the pandemic, but still below historical norms.

Structural Shifts in Global Economics

In addition to inflation, several other long-term trends will shape the future of mortgage rates. Among them is the shift away from globalization. For decades, global supply chains kept inflation low by reducing the cost of goods and services.

Over the past two decades, outsourcing services and manufacturing to Asia, particularly China, significantly reduced costs for G7 nations. By leveraging lower labour costs and relaxed environmental regulations, companies could produce goods and services more cheaply. This, in turn, led to lower consumer prices, contributing to a prolonged period of ultra-low inflation. However, the benefits of this trend were not evenly distributed. While consumers enjoyed lower prices, domestic workers faced wage stagnation as jobs were outsourced overseas. This shift in economic activity contributed to a widening income gap between skilled workers and those whose jobs could be easily offshored.

But with the recent rise of protectionist policies, reshoring, and heightened geopolitical tensions, the global economy could become less efficient. The resulting inflationary pressures may push interest rates higher in the long run.

Larry Summers has been vocal about the risks of what he calls "stagflationary tendencies" in a more fragmented world. "When globalization recedes, prices rise," Summers said in a 2022 speech. He argues that central banks will need to keep a closer eye on inflation than they did during the first two decades of the 21st century, lest the world slip back into the stagflationary conditions of the 1970s.

At the same time, rising government debt—another legacy of both the financial crisis and the pandemic—could push rates up. In the U.S. and much of Europe, government borrowing surged in 2020 and 2021 to finance emergency relief programs. As interest rates rise, the cost of servicing this debt will increase, potentially crowding out other forms of spending. This dynamic could put upward pressure on long-term yields, pushing mortgage rates even higher.

The Role of Central Banks

One key question is how central banks will respond to these challenges.

In Canada, Tiff Macklem, Governor of the Bank of Canada, like his global peers, has been on an aggressive rate-hiking campaign to rein in persistent inflation, raising concerns about the risk of stifling economic growth. Canada's housing market, which had seen rapid price increases during the pandemic, began to cool significantly after rate hikes in 2022 and 2023. This shift has sparked fears of a broader economic slowdown, particularly given the nation's reliance on real estate as a key economic driver. Macklem has acknowledged the difficult balancing act, stating, "Inflation is still too high, and we are committed to getting it back to target. But we also recognize that the higher rates needed to control inflation risk causing a deeper recession." He must now carefully weigh these risks while attempting to guide the Canadian economy through this period of heightened uncertainty.

Rapid rate hikes in 2022 and 2023 caused a slowdown in the housing market, with home sales plummeting and prices beginning to soften.

Jerome Powell, the Chair of the Federal Reserve, has been clear that his priority is bringing inflation back to the Fed's 2% target, even if that means keeping rates higher for longer. "We will stay the course until the job is done," Powell said in 2023, echoing the Fed's hawkish stance.

But the Fed and its counterparts are also acutely aware of the risks of overtightening. Higher interest rates can stifle economic growth, and there is a growing fear that aggressive monetary tightening could trigger a recession. Rapid rate hikes in 2022 and 2023 caused a slowdown in the housing market, with home sales plummeting and prices beginning to soften.

One option on the table for central banks is yield curve control (YCC), a policy tool similar to quantitative easing that involves capping long-term interest rates by purchasing government bonds. The Bank of Japan has used YCC since 2016 with mixed success, and some economists have floated the idea that other central banks could adopt similar measures in future crises. While YCC could help keep mortgage rates low, it also carries risks, including the potential for financial distortions and asset bubbles.

Financial Instability and Risk Premiums

Another wild card is financial market stability. The collapse of several high-profile banks, including Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse, in early 2023 sent shockwaves through the global financial system, raising questions about banks' resilience in a rising-rate environment.

When banks fail, investors demand higher risk premiums to hold long-term debt, which can push up bond yields and, by extension, mortgage rates. This dynamic played out in 2023, when concerns about banking sector instability caused long-term bond yields to rise, even as short-term rates fell in anticipation of central bank rate cuts.

Mohamed El-Erian, Chief Economic Adviser at Allianz, has warned that financial instability could become a defining feature of the post-pandemic world. "We are in an environment of higher volatility and greater financial fragility," El-Erian said in a 2023 interview. He argues that central banks will need to balance their inflation-fighting mandates with the need to maintain financial stability, a task that could prove increasingly difficult as interest rates rise.

The Long-Term Outlook: A New Normal

As we look to the future, it is clear that the era of ultra-low rates is behind us. The structural forces that drove rates down in the years following the financial crisis—globalization, technological innovation, and ample labour supply—are waning, and new pressures, from demographic shifts to supply chain reshoring, are emerging.

The most likely scenario is one in which mortgage rates settle somewhere between their pre-pandemic lows and historical norms. While rates are unlikely to return to the ultra-low levels of 2020 and 2021, they are also unlikely to reach the double-digit heights of the 1980s, barring a major inflationary shock.

Instead, the "new normal" could see mortgage rates stabilizing in the 4-7% range, similar to the period between the dot-com bust and the financial crisis (2001 to 2007).

The "new normal" could see mortgage rates stabilizing in the 4-7% range.

Of course, all of this depends on how inflation, central bank policy, and global economic trends evolve. After over a decade of heavy central bank intervention in financial markets, market signals are weak, and most financial analysts spend more time listening to central bank guidance than looking at economic fundamentals. Suppose central banks step away and allow capitalism and market forces to step back in. In that case, very few employees remain in financial markets who have experience operating in that type of environment.

Takeaways for Homebuyers and Homeowners

This represents a significant shift from the past decade of cheap borrowing costs for homebuyers and homeowners. The days of 3% mortgages are likely over, at least for the foreseeable future. However, while borrowing costs may remain higher than in recent memory, so could the rewards of holding real estate.

The long-term trajectory of interest rates and mortgage costs will depend on a complex interplay of factors—many of them outside the control of central banks. As policymakers navigate this uncertain landscape, one thing is clear: the next decade will look very different from the one that came before.